icons

Rituale

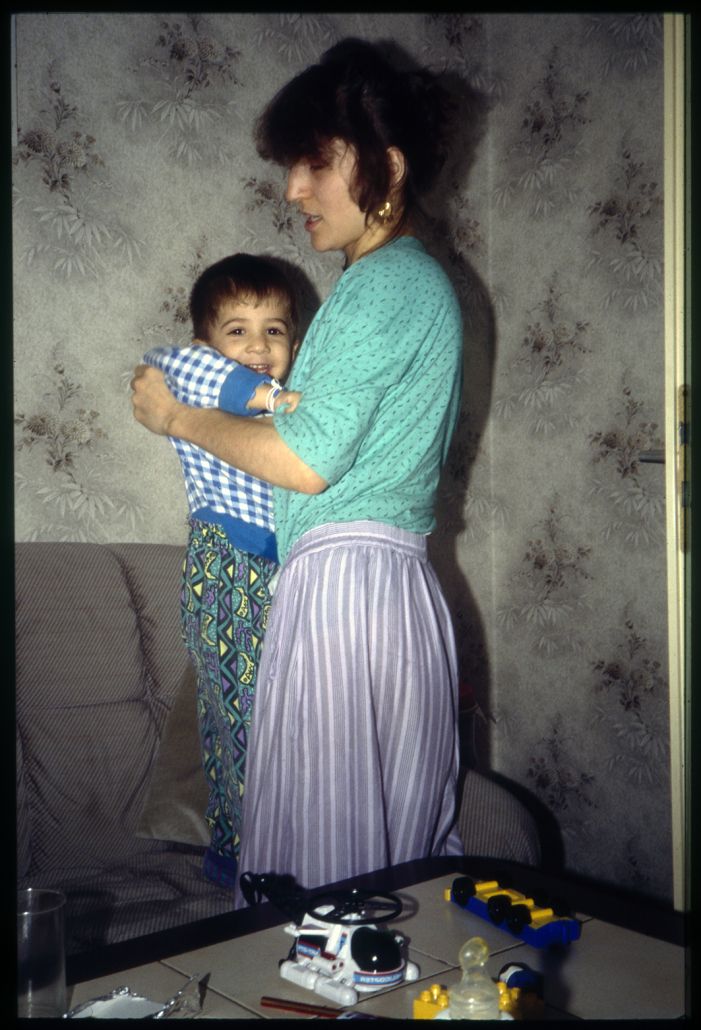

Anziehen. Ausziehen. Morgens. Einen Pullover über den Kopf ziehen. Den Arm in den Ärmel führen. Den anderen Arm in den Pullover zwängen. Ihn dann, obwohl er immer wieder wegrutscht in das Ärmelloch hineinziehen und die kleine Hand ergreifen. Dann die Hand durch die schmale Ärmelöffnung ziehen.

Abends. Den Pullover ausziehen. Das Schlafoberteil anziehen. Die Schlafanzugshose anziehen. Kleine Hände zerren an der Bluse. Zähne beißen sich in Handrücken. Der kleine Körper lässt sich hängen. Der Körper bäumt sich auf. Der Körper windet sich. Die Hände, beide Arme, die Beine, der Mund und die kleinen Zähne sind überall und nichts ist zu fassen.

Anziehen. Ausziehen. Ziehen. Er zieht. Sie zieht, zerrt, schiebt. Er windet sich, gleitet aus den Händen, läuft in ihre Arme, er hält sich fest, will gehalten werden, stößt sich ab. Fäuste ballen, Hände greifen ineinander, Köpfe berühren sich. Alltägliche Choreografie. Und das Wissen, das es so ist, dass man sich fasst, ringt, umringt, Mutter und Kind ist.

Der Vater sieht zu und nimmt den Fotoapparat. Für ihn ist es ein Blick auf eine abendliche Zeremonie, die ihm zeigt, dass er einen lebendigen Sohn hat, dass seine Frau sich um ihn kümmert. Er fotografiert einen tagtäglichen Akt zwischen Mutter und Kind. Jene Verstrickung von Nahsein und Fremdsein, von unzähligen Handlungen, in denen die Körper aufeinander bezogen sind, die Rollen erprobt und jeden Tag neu festgelegt werden.

Diese Privatfotografie öffnet den Blick auf ein alltägliches Ritual in einer familiären Welt. Die Handelnden halten ihre Rollen ein, die zeitlichen Abläufe sind festgelegt – in diese intime Welt alltäglicher Rituale schaut der Betrachter hinein.

Birgit Szepanski

Rituals

Dressing. Undressing. Mornings. Pulling a sweater over his head. Getting an arm into a sleeve. Wedging the other arm into the pullover. Then, even though it always slips out, pulling it into the sleeve and grabbing the little hand. Then pulling the hand into the narrow sleeve opening.

Evenings. Taking off the pullover. Putting on the pyjama top. Putting on the pyjama bottoms. Little hands pulling on the blouse. Teeth biting into the backs of hands. The little body goes limp. The body rears up. The body twists and turns. The hands, both arms, legs, mouth and the little teeth are everywhere and nowhere to be held.

Dressing. Undressing. Pulling. He pulls. She pulls, tugs, shoves. He twists, slips away from her hands, runs into her arms, he holds on tight, wants to be held, pushes himself away. Fists clench, hands grab each other, head touch. Everyday choreography. And knowing that it’s like this, that one grabs, struggles, surrounds, is mother and child.

The father watches and picks up the camera. For him, the view is an evening ceremony that shows him that he has a living son, and that his wife looks after him. He photographs a daily ritual between mother and child. That entanglement of intimacy and distance, of countless actions where bodies relate to each other, roles are tried out and re-established every day.

This private photograph opens up the view of a daily ritual in a familiar world. The actors stick to their roles, the temporal sequences are fixed – in this intimate world of daily routines, the observer peers in.

Birgit Szepanski

Bilder mit Migrationshintergrund

Orientalische Folklore: Maria mit dem Jesuskind vor dem Schlafengehen. Der offene Blick, das Lächeln des Jungen auf den Fotografen gerichtet, der sein stolzer, fröhlicher Vater sein könnte. Die Mutter: ganz in Kontakt mit dem Kind, eingetaucht in diese unvorstellbaren orientalischen Muttergefühle, ganz diesen Moment genießend, auch und gerade das Fotografiert-werden dabei mit geschlossenen Augen. Dieses „Überschwemmt-sein-von-Emotionen“! … – Dieses Bild ist wie eine Mutter-Kind-Ikone. Das heißt: Man kann seine Gefühle dahingehend auslagern. Wir wissen ja: Mutter-Kind-Gefühle oder auch Vater-Mutter-Kind-Gefühle lassen sich in unserer Kultur am besten immer in den Orient auslagern/“immigrieren“. Maria und dieses Jesuskind aus Palästina zum Beispiel sind seit 2000 Jahren die wirklichen Migrationshintergründe für unsere wirklichen Gefühle. Diese Fotografie macht sie sichtbar, könnte man sagen und dazu eine Theorie des Verstehens entwerfen, eine Theorie des Sich-Verstehens-in-Bildern. Eine Theorie des Sich-Selbst-im-sich-Fremd-Verstehens-in-Fotografien, eine Theorie der unbewussten Abspaltung und der Reintegration.

Und man könnte auch auf die Krise der ethnografischen Repräsentation zu sprechen kommen in diesem Bild-Zusammenhang, auf die Frage, was wir eigentlich tun, wenn wir wirklich ins ethnologische Feld gehen und die „wirklichen“ sozialen Umrisslinien für den Bildgebrauch in fremden Kulturen erforschen. – Was wir wirklich tun, wenn wir Theorien darüber entwerfen, wie bestimmte Bildherstellungs- und Bildbenutzungs-Praxen (das Aufnehmen, das Verschenken, das An-die-Wand-Hängen oder -Werfen oder -mit-Dart-Pfeilen-Bewerfen, das Zerreißen, Verbrennen, Einrahmen, Übermalen oder Weiterverschenken von Fotos) soziale Beziehungen stiften oder steuern oder zumindest stiften oder steuern sollen, in den Augen der Akteure. Und man könnte dann eine Anthropologie der Gefühle oder eine Kulturhermeneutik anschließen – eine Kulturhermeneutik der fotografischen Horizontverschmelzung oder der unaufhebbaren Differenz. Und man könnte sich die Frage stellen, wie wir produktiv mit der eurozentrischen Behauptung umgehen, dass erst die westliche Kultur so reflexiv geworden ist, dass sie ihre eigenen sozialen und kulturellen Bedingtheiten, ihre eigene fundamentale Kontingenz, radikal zu thematisieren und zu fotografieren vermag.

Bilder sind Migrationsanlässe für unser Denken.

Rainer Totzke

Pictures with a migration background

Oriental folklore: Mary with the Baby Jesus before bedtime. The open expression, the boy’s smile towards the photographer who could be his proud, happy father. The mother: in close contact with the child, immersed in unimaginable, Oriental feelings of motherhood, taking full pleasure in the moment, especially and including the moment of being photographed, taking part with closed eyes. This “being-inundated-by-emotions!” This picture is like a mother-child icon. This means one can export one’s feelings in this direction. Because we know that mother-child feelings and even father-child feelings in our culture are always best exported or “immigrated” to the Orient. For 2000 years for example, Mary and Baby Jesus from Palestine have been the real migration backgrounds for our real feelings. This photograph makes them visible, you could say, and thereby formulate a Theory of Understanding, a Theory of Understanding Oneself in Pictures. A Theory of Understanding-Oneself-In-Understanding-One’s-Foreignness-In-Photographs, a theory of unconscious separation and reintegration.

And in the context of this picture, you could also comment on the crisis of ethnographic representation, on the question of what we actually do when we really go into the field of ethnology and research the “real” social contours of image use in foreign cultures; what we really do when we create theories about how certain practices of image creation or image use (capturing them, giving them as presents, hanging/throwing them on/at the wall, throwing darts at them, ripping them up, burning, framing, painting over them or handing them down) promote or guide social relations, or at the least how they should promote or guide them in the eyes of the participants. And one could link an anthropology of feelings or cultural hermeneutics – a cultural hermeneutics of the photographic “fusion of horizons”* or irrevocable difference. And one could ask oneself how to deal productively with the Eurocentric claim that Western culture has became so reflexive, that it is able to address and photograph its own social and cultural conditionality, its own fundamental contingency.

Pictures are occasions for the migration of our thinking.

Rainer Totzke

*This is a term coined by Hans-Georg Gadamer, a German philosopher of the continental tradition.